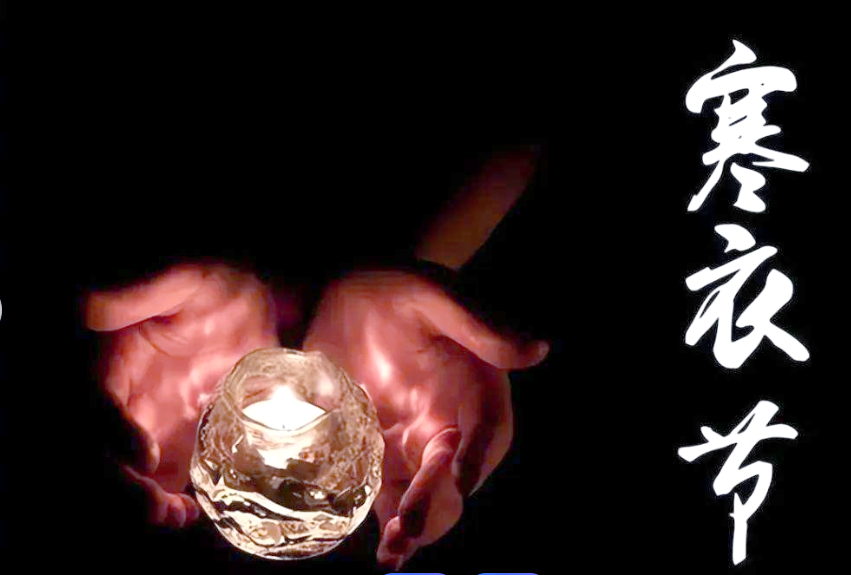

Among China’s traditional festivals, the Winter Clothing Festival stands out as a solemn yet heartfelt occasion for ancestor worship. Centered on the ritual of “sending warm clothes to deceased relatives”, it embodies the Chinese people’s emotional pursuit of “honoring the deceased and cherishing their virtues”, serving as an important cultural link connecting life and death, and conveying longing as autumn transitions to winter. On the 1st day of the 10th lunar month each year, as cold winds rise and nature fades, Chinese people celebrate the festival with solemn rituals—sending “winter clothes” to their ancestors to pray for protection, inheriting family culture, and strengthening family bonds. For foreign travelers visiting China during this period, witnessing these unique folk customs offers an in-depth insight into the Chinese reverence for life cycles and family heritage.

The origin of the Winter Clothing Festival can be traced back to ancestor worship and agricultural rituals in ancient times. After thousands of years of evolution, it integrated Taoist concepts and folk beliefs, eventually forming fixed customs. The 1st day of the 10th lunar month marks the transition from autumn to winter. The ancients believed that as yang energy declined and yin energy prevailed, the cold winter would arrive, and their deceased relatives would suffer from the cold in the underworld. Thus, they prepared clothes to keep them warm, laying the foundation for the “sending winter clothes” ritual. Taoism classified the festival as one of the “Three Ghost Festivals” (along with Qingming Festival and Zhongyuan Festival), believing that the gate of the underworld opens on this day, allowing ancestors to receive offerings from the mortal world. Folks then developed rituals such as ancestor worship, burning paper clothes, and offering sacrifices, gradually linking the festival to the core meanings of “keeping warm, praying for blessings, and practicing filial piety”. By the Ming and Qing dynasties, the customs had spread across the country, with regional variations but unchanged core values of “sending warmth to ancestors and honoring them”.

“Burning winter clothes” is the most iconic custom of the festival, a solemn ritual filled with deep emotions. The “winter clothes” are mostly made of paper, including cotton-padded jackets, trousers, shoes, and hats. Some families also prepare paper bedding, money, houses, and other items, symbolizing a worry-free life for ancestors in the afterlife. Before the festival, every household prepares these paper clothes, incense, candles, and sacrifices. On the festival day, they visit ancestral cemeteries, clan halls, or hold rituals in front of ancestral memorial tablets at home: first burning incense to pay homage, expressing longing and blessings to ancestors, then burning the paper clothes and other items in designated areas, believing that flames can deliver these offerings to the ancestors. Today, to promote environmental protection and fire safety, many regions have advocated civilized ways of worship, such as replacing paper-burning with flowers and ribbons, or gathering at designated burning spots. This preserves the festival’s essence while ensuring public safety.

Ancestor worship and praying for blessings are another important ritual, complementing “burning winter clothes”. On the festival day, families carefully prepare sacrifices, mostly fruits, pastries, wine, and meat that the ancestors loved. In some regions, warm porridge and meals are also prepared, symbolizing dispelling the cold for ancestors. During the ritual, younger generations kowtow in order of seniority, expressing gratitude and respect to their ancestors, and praying for their blessings for the family’s safety, health, and abundance in the cold winter. Some clans also take this opportunity to gather, recall the deeds of their ancestors, and pass down family traditions, making the festival a link connecting intergenerational emotions.

In addition to the core rituals of ancestor worship and burning winter clothes, various regions have unique customs that add diversity to the festival. In parts of northern China, eating dumplings is a tradition on the Winter Clothing Festival. Dumplings, shaped like ingots, symbolize accumulating blessings and warmth for the family and ancestors. In some rural areas, small temple fairs are held, inviting Taoists to chant scriptures and pray for the village and clan to ward off disasters. In some southern regions, people burn “winter clothes” by rivers, believing that flowing water can carry their longing to the ancestors. Though different in form, these customs all revolve around the core of “remembrance, prayer, and warmth”, showcasing the cultural characteristics of different regions.

For foreign travelers, when participating in or observing Winter Clothing Festival activities, it is crucial to prioritize safety and etiquette, and respect local customs and cultural taboos. Firstly, the festival rituals are solemn. Whether at cemeteries, clan halls, or worship sites, keep quiet, avoid laughing loudly, or taking photos casually. If you want to record the scene, ask for permission from locals in advance. Secondly, activities like burning paper clothes must comply with local regulations and be carried out in designated areas. Do not burn items without permission to avoid fires, and actively choose civilized ways of worship such as offering flowers. In addition, some regions have folk taboos for the festival, such as not touching sacrifices casually or wandering randomly in worship venues. Respecting these details will help you better integrate into the local atmosphere.

The Winter Clothing Festival is not merely a worship ritual; its essence is a cultural activity carrying longing and gratitude. As winter approaches, it reminds people not to forget the kindness of their ancestors, unites family emotions in remembrance, and conveys reverence for life through rituals. For foreign travelers, experiencing the festival’s customs allows them to witness the traditional Chinese concept of “treating the deceased as the living” and feel the Chinese people’s profound emphasis on family love and inheritance. This “warmth-sending appointment” across life and death is not only a tribute to ancestors but also a celebration of life’s true essence, offering every participant a unique cultural insight.

暂无评论内容