As one of the “Eight Great Arts of Yanjing”, Beijing Ivory Carving, together with Jade Carving, Cloisonné and Lacquer Carving, is known as one of the “Four Great Treasures” of Beijing arts and crafts. Since its birth, it has become an exclusive imperial art treasure due to the rarity of its material and the sophistication of its craftsmanship. From ivory hairpins in the Shang Dynasty to imperial artifacts in the Qing Dynasty, this craft has spanned thousands of years, engraving the delicacy and elegance of Eastern aesthetics in the fingertips of craftsmen. Today, though facing inheritance challenges due to material protection, it still gains new vitality in persistence, waiting for travelers to explore the imperial charm hidden in its exquisite texture.

The history of Beijing Ivory Carving is time-honored. Archaeological discoveries show that the Upper Cave Man in Zhoukoudian was buried with ivory carving ornaments, and the “Records of the Grand Historian” also records that “King Zhou first made ivory hairpins”, confirming its history of at least 3,000 years. Early ivory carvings were mostly practical objects such as tally boards and paperweights with relatively simple craftsmanship, and it was not until the Qing Dynasty that it reached the peak of its craftsmanship. At that time, the Imperial Workshop of the Qing Palace set up a special institution for ivory carving. The emperor personally instructed the design, court painters drew the drawings, and craftsmen carved according to the drawings, making the ivory carving works possess both imperial dignity and artistic height. The varieties also expanded to ornaments, jewelry, stationery and other items, creating many famous craftsmen and forming a dignified, delicate, magnificent and luxurious imperial style.

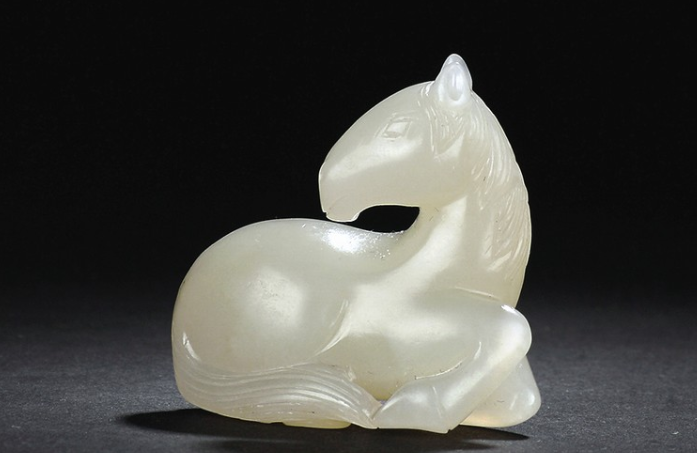

The excellence of Beijing Ivory Carving is embodied in three categories: carving, inlaying and weaving, each of which fully shows the craftsmanship of the artisans. Carving is the core technique, including relief carving, round carving, openwork carving, micro-carving, etc. Among them, openwork carving is the most amazing. Craftsmen need to carve meticulously on ivory pieces as thin as cicada wings to create complex and exquisite patterns with layers as fine as hair. The inlaying technique combines ivory with jade, gold and silver to create diverse textures; the weaving technique is even more legendary. It requires soaking ivory to soften it, splitting it into silk threads less than 0.1 cm wide and weaving them into shape. Due to the huge time and cost, Emperor Yongzheng issued an edict to stop its production. Today, only two ivory woven fans are collected in The Palace Museum, becoming a lost art.

In the late Qing Dynasty and early Republic of China, Beijing Ivory Carving gradually moved from the imperial palace to the people. More than a dozen ivory workshops gathered around Huashi Street, among which Geng Runtian, known as “Gengzi”, was the most renowned. He inherited imperial craftsmanship, was good at three-dimensional round carving, and had high attainments in maid and arhat themes. In the 1930s, when the industry was prosperous, there were more than 100 employees. After the establishment of Beijing Ivory Carving Factory, it became an important force for the country to earn foreign exchange. A high-quality ivory carving could once be exchanged for a Volga car, with the saying that “one ivory carving factory is equivalent to half of Shougang Iron and Steel Company”. It was also used as a national gift to foreign leaders many times.

In the 1990s, China joined the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), banning the import and trade of ivory. Beijing Ivory Carving was on the verge of extinction, with the number of employees dropping from more than 800 to less than 40. Fortunately, generations of craftsmen have persisted. Chai Ciji, a national-level intangible cultural heritage inheritor, is a core representative. He studied under the famous artist Sun Sen, combining traditional round carving with modern shallow and deep relief carving and openwork carving. His works such as “Nüwa” and “Imperial Concubine of the Tang Dynasty” continue the artistic blood with elegant style and rich connotation. Today, craftsmen mostly use legal alternative materials such as mammoth ivory, adhering to the essence of craftsmanship while practicing the concept of ecological protection.

For foreign travelers, there are several must-visit places to explore the charm of Beijing Ivory Carving. The Palace Museum collects a large number of exquisite imperial ivory carvings from the Qing Dynasty, from magnificent ornaments to exquisite stationery, showing the peak craftsmanship; the Ivory Carving Boutique on the 4th floor of Beijing Arts and Crafts Building gathers works by masters such as Chai Ciji and Yang Chunhe, including large pieces carved from whole ivory and old handcrafted works from the 1970s and 1980s, which are of great ornamental and collection value; Beijing Ivory Carving Factory, which sticks to its original site in Huashi, although not as large as before, still retains the “root” of ivory carving craftsmanship, allowing visitors to explore the marks of the industry’s ups and downs.

Today’s Beijing Ivory Carving has long surpassed the material itself and become a living fossil carrying craftsmanship and culture. Under the premise of compliance, craftsmen delve into the craftsmanship, restoring traditional techniques and trying to integrate with modern aesthetics, making this thousand-year-old craft gain new vitality in persistence. When you stare at the delicate texture and vivid patterns of ivory carving works, you can understand the spiritual core of Eastern craftsmen’s “pursuit of perfection” and feel the artistic shock spanning time and space.

暂无评论内容